Menu

Free Consultation

A cavit tooth can go from a faint twinge to an all-night throb in a matter of hours, because once decay eats through the enamel and into the pulp the trapped swelling presses directly on the tooth’s nerve.

In this article you’ll learn the real difference between tooth decay and cavities, how to recognise a cavitated tooth before the damage deepens, science-backed methods to stop or even remineralise early lesions, which “natural” remedies help (and which don’t), plus the dentist-approved daily habits that keep cavity tooth decay from returning.

The terms "cavit tooth" and "cavitated tooth" are often confused, but they refer to very different things — and understanding the difference is important when seeking proper dental care.

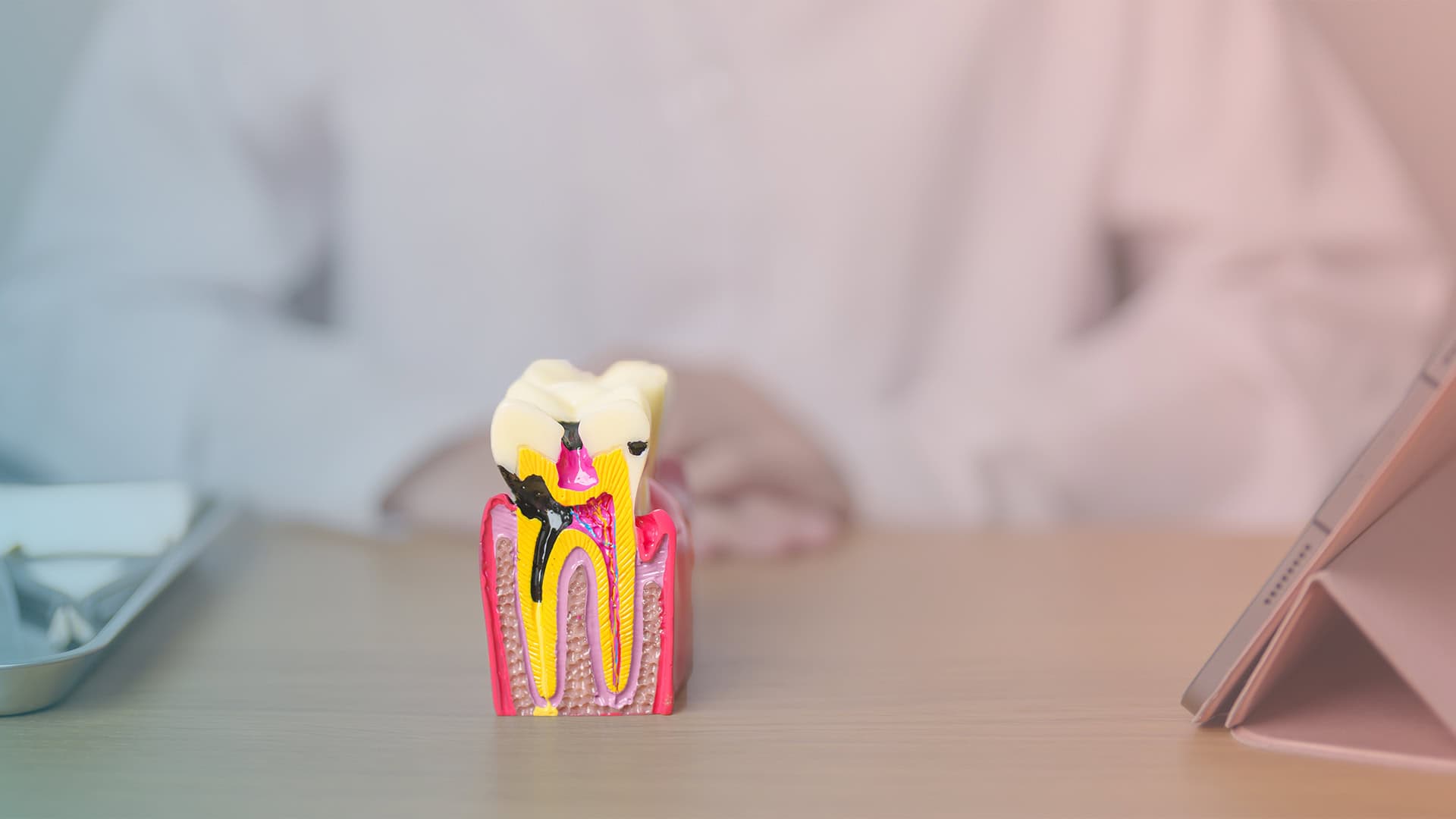

A cavitated tooth refers to a tooth that has developed an actual physical hole or opening in the enamel or dentin as a result of tooth decay. In dental terminology, cavitation is the point at which the decay has progressed beyond early, reversible stages and caused permanent structural damage. At this stage, the tooth cannot heal on its own and typically requires professional treatment such as a filling, crown, or in severe cases, a root canal.

On the other hand, the term “cavit tooth” is not a clinical diagnosis but is commonly used to refer to a decayed or damaged tooth—especially when someone is experiencing pain or visible damage. However, “Cavit” is also a trademarked brand of temporary dental filling material. It’s frequently used by dentists as a short-term solution to seal a cavity between appointments, during root canal procedures, or while waiting for permanent restorations. Cavit material is not a permanent fix; it’s designed to protect the tooth temporarily while preventing bacteria and debris from worsening the decay.

So, while a cavitated tooth describes the condition of the tooth, Cavit refers to the product used to manage that condition temporarily.

Key takeaway: If you’re experiencing symptoms like sensitivity or visible holes in your tooth, it’s important to distinguish between the condition (cavitation) and any temporary treatments (such as Cavit) used to manage it before permanent care is provided.

The terms tooth decay and cavities are often used interchangeably, but they aren’t exactly the same. While closely related, one refers to the process, and the other refers to the result.

Tooth decay is a progressive disease that begins when the bacteria in your mouth feed on sugars and produce acids. These acids attack and demineralise the outer surface of the tooth — the enamel. Over time, repeated acid attacks lead to the loss of minerals from the enamel in a process known as demineralisation.

At this early stage, the damage is reversible with good oral hygiene, fluoride use, and dietary changes. However, if the demineralisation continues unchecked, the enamel breaks down and a small opening forms. This leads to cavitation, or the development of a cavity.

A cavity is the physical hole or structural damage that forms in a tooth as a result of advanced tooth decay. Once a cavity develops, it cannot heal naturally and requires dental treatment to restore the tooth’s structure and function. If left untreated, the cavity can expand into deeper layers of the tooth, eventually affecting the dentin and pulp, leading to pain, infection, or tooth loss.

Dentists use tooth decay to describe the ongoing pathological process caused by bacterial activity, while cavity refers to the visible or detectable damage resulting from that process.

In simple terms:

Understanding this distinction can help patients seek treatment earlier, potentially reversing decay before it causes permanent cavities.

Cavity tooth decay is a widespread dental issue caused by a combination of biological, lifestyle, and environmental factors. Understanding what leads to decay can help you take effective steps to prevent it.

The primary cause of tooth decay is plaque — a sticky biofilm made up of bacteria, food particles, and saliva. When you eat sugary or starchy foods, bacteria in plaque produce acids that begin to break down your tooth enamel. If plaque isn’t removed through daily brushing and flossing, this acid attack continues and leads to demineralisation and eventually cavitated lesions (cavities).

[Source: Healthline, 2023]

Diets high in refined sugars, sticky snacks, sugary drinks (like soda or energy drinks), and frequent snacking increase the risk of cavity formation. Bacteria feed on these sugars and produce acid for up to 20–30 minutes after every meal or sip — especially harmful if you consume sugary items throughout the day.

Saliva plays a key role in neutralising acids, washing away food debris, and providing essential minerals for tooth repair. People with xerostomia (dry mouth) — often caused by medications, smoking, aging, or medical conditions — are more vulnerable to rapid cavity development due to reduced natural protection.

Fluoride strengthens tooth enamel and makes it more resistant to acid attacks. Lack of fluoride in drinking water, toothpaste, or professional treatments increases your risk of decay. Fluoride-deficient individuals are less equipped to remineralise enamel after daily acid exposure.

Genetics can influence your enamel hardness, saliva composition, and mouth bacteria balance — all of which impact your risk for cavity tooth decay. Some people naturally have deeper grooves in their teeth or a higher number of cavity-causing bacteria, making them more susceptible despite good oral hygiene.

Certain populations are more likely to experience rapid or frequent decay:

Cavity tooth decay doesn’t happen overnight — it’s the result of long-term exposure to acid-producing bacteria and lifestyle habits. Knowing your risk factors is the first step toward prevention.

Cavities don’t form overnight — tooth decay develops in stages, starting subtly and progressing to permanent damage if left untreated. Recognising the difference between early-stage tooth decay and a cavitated tooth can help you seek timely care and potentially avoid fillings altogether.

In the early stages, decay begins as white-spot lesions on the enamel. These chalky, pale areas often appear near the gum line or in the grooves of molars and are caused by demineralisation, where acids dissolve calcium and phosphate minerals from the tooth surface.

At this stage:

If the demineralisation process continues, it breaks through the enamel and forms a cavity — a physical hole in the tooth structure. This is known as a cavitated tooth, and it requires dental intervention to stop further deterioration.

Common signs and symptoms of a cavitated tooth include:

At this point, the decay has reached deeper layers of the tooth often the dentin — and may progress toward the pulp if not treated, leading to more severe pain or infection.

In summary:

Recognising these signs early can save you time, money, and discomfort — and may even allow you to stop a cavity before it forms.

The good news is that tooth decay can be stopped and even reversed but only in its early stages. Once the damage progresses into a full cavity (i.e. cavitation), healing requires professional intervention. Here's what science tells us about managing both stages:

In the earliest stage of tooth decay — where enamel demineralisation has occurred but no hole has formed it's still possible to rebuild and harden the enamel. This process is called remineralisation.

Evidence-backed methods include:

These methods are most effective when decay is limited to white-spot lesions and there’s no visible hole yet.

Once decay progresses past the enamel into the dentin and forms a cavity, remineralisation is no longer enough. At this stage, dental restoration is required to remove decayed material and rebuild the tooth.

Common treatments include:

In cases where treatment is being done in stages (e.g., during root canal therapy or when multiple cavities are being addressed over time), dentists may use Cavit®, a temporary filling material. Cavit seals the cavity to:

It’s a valuable short-term tool but not a substitute for long-term dental care.

Bottom line:

Acting early makes all the difference. The sooner you catch decay, the better your chances of avoiding the drill.

The idea of reversing cavities and tooth decay naturally has gained popularity online, but what does the science actually support — and what’s just wishful thinking?

Let’s break down the evidence behind popular natural remedies and where their limits lie.

When decay is still in its non-cavitated stage (white-spot lesions), natural methods can help support remineralisation — but they cannot fill an actual hole in the tooth. Here's what shows some promise:

While the above practices may help halt or slow early decay, they:

Any visible hole, persistent pain, or sensitivity must be evaluated by a dentist.

Safe & Helpful (complementary):

Unproven or risky:

Yes — you can support early-stage healing of tooth decay naturally with the right diet and habits. But once a cavity forms, only a dentist can restore the tooth. Natural methods work best alongside professional care, not as replacements for it.

While cavities are common, they’re largely preventable with a combination of consistent oral hygiene, dietary awareness, and professional care. Here's how to stop tooth decay and cavities before they start — and keep your smile healthy for life.

Brushing twice daily with a fluoride toothpaste is your first line of defence. Fluoride helps:

Flossing once a day is equally important, as it removes plaque and food particles from between teeth where brushes can’t reach — a common site for hidden decay.

Tip: Use a soft-bristled toothbrush and replace it every 3 months.

Sealants are thin, protective coatings applied to the chewing surfaces of back teeth (molars) — which are more prone to trapping food in their grooves.

Tooth decay thrives on frequent sugar exposure — especially from sugary drinks, candies, dried fruits, and refined carbs.

Preventive diet tips:

Chewing sugar-free gum (especially with xylitol) after meals also helps neutralise acids and stimulate saliva.

Even with good home care, professional cleanings every 6 months are essential to:

Fluoride in tap water has been shown to reduce tooth decay in populations by 25% or more.

However, it remains a controversial topic in some communities. While most health organisations — including the WHO, ADA, and CDC — endorse water fluoridation as safe and effective, some opponents argue about dosage control and long-term exposure concerns.

If you live in an area without fluoridated water, talk to your dentist about fluoride supplements or treatments.

Takeaway: Preventing cavities and tooth decay is all about consistency — brush and floss daily, eat wisely, visit the dentist regularly, and leverage preventive tools like fluoride and sealants. These small habits add up to lifelong dental health.

Tooth decay and cavities may be common, but they’re also highly preventable — and in early stages, even reversible. Whether you're dealing with a cavitated tooth or aiming to protect your enamel long-term, the right knowledge and habits can make all the difference.

If you’re noticing tooth sensitivity, dark spots, pain while chewing, or visible holes, these may be signs of a cavit tooth — and it's time to book a dental check-up.

Prompt care can save the tooth and prevent further damage or infection.

Prevention and early intervention are always easier — and more affordable — than waiting until a problem worsens.

Stay proactive, stay consistent, and don't skip your dentist appointments.